The charango is a small stringed instrument originating from the Andean regions of South America. It is traditionally made from the shell of an armadillo, although modern versions can be constructed from other materials such as wood.

What is Charango: Table of Contents

Welcome to a musical journey that takes us deep into the heart of the Andean mountains. Today, we spotlight an instrument that’s small in size but large in cultural impact: the charango. With a distinctive sound that resonates across the high plains of South America, the charango holds a special place in the diverse world of music.

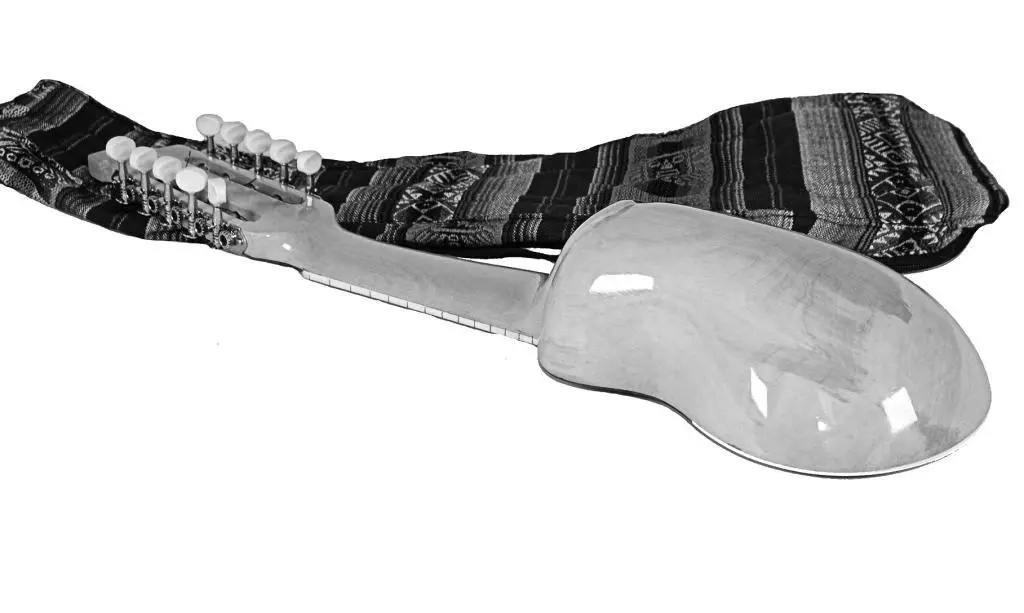

The charango is an Andean stringed instrument that, while compact, carries a rich, vibrant sound that has echoed through the mountains and valleys of the Andes for centuries. About 66 cm (26 in) long, it traditionally features ten strings in five courses, though you’ll find variations in different regions. Its body was traditionally crafted from the shell of an armadillo, but modern instruments are more commonly made from wood, which some believe offers better resonance. Regardless of the material used, each charango carries a piece of history, a snippet of a melody that links the present to the past.

However, to truly appreciate the charango, one must look beyond its physical characteristics and into its cultural and historical significance. The charango is more than just an instrument; it’s a symbol of resilience, cultural identity, and the enduring spirit of the Andean people. Introduced to the region during the colonial period, it’s a testament to the synthesis of indigenous and Spanish influences that shaped the Andean culture.

The charango has deep roots in Andean culture, particularly within Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, northern Chile, and northwestern Argentina. It’s not just a musical instrument in these regions; it’s a social tool, a vehicle for storytelling, and a companion in celebrations and gatherings. Its sound, reminiscent of the Andean landscapes from where it originates, evokes emotions that words often cannot.

In the hands of a skilled player, or charanguista, the charango tells stories of love, struggle, joy, and sorrow, painting a sonic picture of life in the Andes. It’s embedded in the fabric of Andean society, a constant companion in festivals and an integral part of their musical education.

History of the Charango

The story of the charango takes us on a fascinating journey back in time, immersing us in the ancient world of the Andean regions. Its history is as rich and varied as the landscapes from which it emerged.

The charango’s roots can be traced back to the indigenous Quechua and Aymara populations that inhabited the Altiplano, a highland plateau that spans across parts of Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, northern Chile, and northwestern Argentina. However, the charango as we know it today didn’t come into existence until the Spanish arrived on South American shores during the colonial period.

When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in South America, they brought with them a variety of European stringed instruments, notably the vihuela—an ancestor of the classical guitar. These instruments would have a profound influence on the indigenous music of the Andean people, leading to the creation of a unique musical instrument—the charango. But the journey from the vihuela to the charango wasn’t straightforward.

There are several theories about how the charango came to be. One suggests that the indigenous musicians were fascinated by the sound of the vihuela but lacked the technology to shape the wood in the same manner. This led them to innovate, using what was readily available to them—armadillo shells—to create a smaller, more portable instrument that had a similar sound. This theory is supported by the fact that traditional charangos were made from armadillo shells.

Another theory proposes that the creation of the charango was an act of defiance. It is suggested that the Spanish colonialists prohibited the indigenous people from practicing their ancestral music. In response, the locals created an instrument that could be easily concealed under a garment such as a poncho, thus allowing them to continue their musical traditions in secret.

Unfortunately, the absence of clear historical documentation makes it difficult to confirm any single origin story. Adding to this complexity is the fact that the modern states of Peru and Bolivia, two countries that are often associated with the charango, had not yet been established during the time of its creation. This has led to ongoing debates among nationalists from both countries about the exact birthplace of the charango.

Despite these debates, there is a consensus among historians that the charango came into its current form around the early 18th century, likely in the city of Potosí in what is now Bolivia. The first documented reference to the charango dates back to 1814, when a cleric from Tupiza noted that the local indigenous population used “guitarrillos mui fuis,” which they called “Charangos,” with great enthusiasm.

Over the centuries, the charango has continued to evolve, adapting to changing cultural contexts and musical styles. Today, it stands as a testament to the enduring creativity and resilience of the Andean people, a vibrant link between their past, present, and future. As we delve further into the charango’s rich history, we will discover how this seemingly simple instrument has played a crucial role in shaping the cultural identity of the Andean region.

Anatomy of the Charango

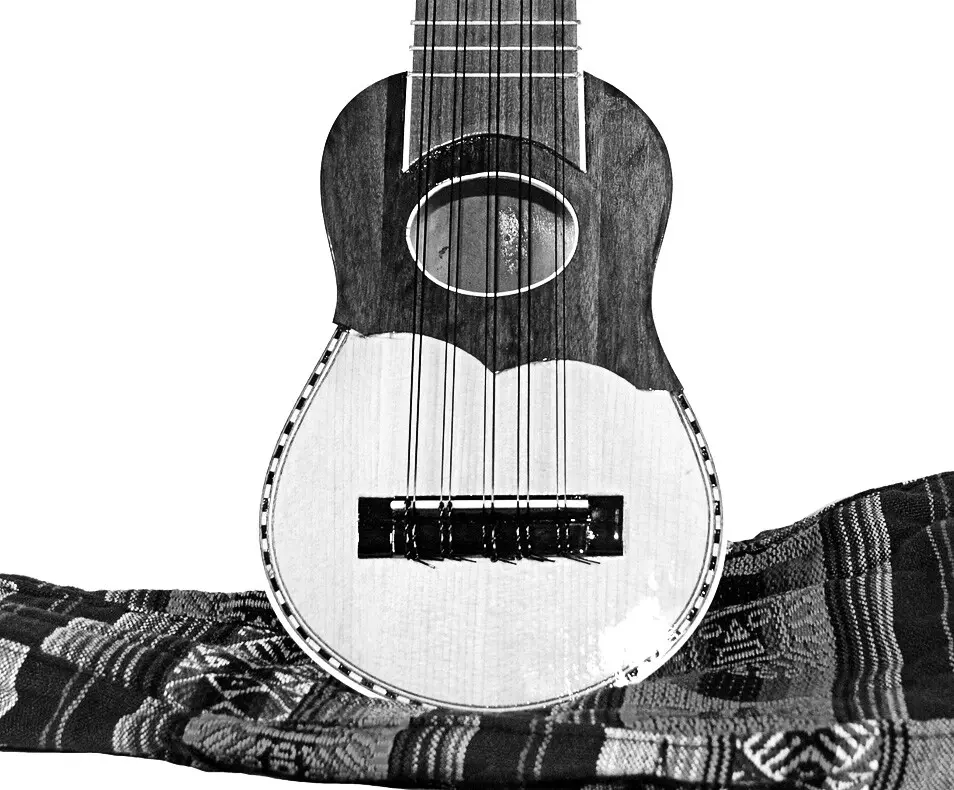

The charango, with its distinctive form and rich timbre, is a marvel of musical craftsmanship. Its design is a unique fusion of indigenous ingenuity and European influences that have culminated in an instrument as compelling to look at as it is to listen to.

Physically, the charango is a small stringed instrument, measuring about 66 centimeters or 26 inches long. Its size makes it compact and easy to handle, a feature that has contributed to its widespread use across the Andean region. It belongs to the lute family, a group of stringed instruments characterized by a deep round back and a flat fretted neck.

One of the most distinctive aspects of the charango is the material used for its construction. Traditionally, the back of the charango was made from the shell of an armadillo, known as quirquincho or mulita in South American Spanish. The use of armadillo shells provided a unique resonance that contributed to the charango’s distinctive sound. However, over time, the use of armadillo shells has become less common due to ethical considerations and the increasing scarcity of armadillos.

Today, charangos are most commonly made from different types of wood, each offering its own unique qualities to the sound of the instrument. Woods such as mahogany, maple, chestnut, and oak are popular choices, each contributing their own character to the charango’s tone. For instance, maple offers a beautiful visual aesthetic, chestnut provides incredible sonority, and oak, while not typically considered a tonewood, has proven to be an excellent choice for a charango body due to its unique acoustic properties. These woods are not only chosen for their acoustic qualities, but also their durability and resistance to warping, ensuring the instrument can stand the test of time.

The charango’s strings are another key component of its anatomy. Unlike most stringed instruments which have four to six strings, the charango boasts a total of ten strings. These strings are arranged in five courses, or pairs, and each pair is tuned to the same note. This arrangement is one of the features that gives the charango its unique sound.

The strings are typically tuned to G, C, E, and E settings from the top of the instrument. Understanding this tuning arrangement is essential for anyone learning to play the charango, as it allows them to navigate the fretboard and produce the desired notes and chords. However, it’s important to note that while the string arrangement and tuning may appear similar to a guitar, the charango has its own unique playing techniques that set it apart.

Making a Charango

The creation of a charango is as much a work of art as the music it produces. The process combines traditional techniques passed down through generations with modern adaptations, resulting in an instrument that beautifully embodies the heritage of the Andean region.

The traditional method of making a charango involved crafting the back of the instrument from the shell of an armadillo. This was a process that required a specific set of skills, as well as a deep understanding of the materials and their acoustic properties. However, as concerns over animal conservation have grown, this method has become less common. Nowadays, charangos are predominantly made from wood, which offers a wide range of tonal possibilities and is more sustainable.

The process of making a charango begins with selecting the right wood. There is a multitude of types to choose from, each with its own unique properties. Mahogany is a common choice due to its stability and resistance to warping. Maple, with its beautiful grain patterns, offers both visual appeal and a balanced tone. Chestnut is known for its incredible sonority, and oak, though not a traditional tonewood, is praised for its resonance when used in charango construction.

Once the wood is selected, a block is carefully shaped to form the body of the charango. This involves hollowing out the block and crafting the delicate curves that give the charango its distinctive silhouette. The dimensions of the block should exceed the final body size by about an inch in each dimension to allow for refining the shape.

Next comes the intricate task of crafting the charango’s neck and fretboard. The neck must be carefully carved and sanded to achieve a comfortable shape that facilitates easy playing. The fretboard, usually made from a harder wood for durability, is then attached to the neck. Precise measurements are necessary to ensure accurate placement of the frets, which will influence the intonation and playability of the instrument.

The soundboard, or top of the charango, is then attached to the body. This part of the instrument is critical in producing the charango’s unique sound, and its construction requires a great deal of precision. Once the soundboard is attached, the soundhole is carefully cut out.

Finally, the charango’s ten strings are added. They are usually made from nylon or gut and are arranged in five pairs. Each pair is tuned to the same note, creating a chorus-like effect when played.

Playing the Charango

Learning to play the charango is an adventure in musical exploration. As with any instrument, it requires a blend of technique, practice, and a touch of creativity. This small Andean instrument with its ten strings, arranged in five pairs, may seem daunting at first glance, but once you familiarize yourself with its unique characteristics, you’ll find it a joy to play.

The first step in playing the charango is understanding its string arrangement. Unlike a guitar, the charango’s strings are organized from the top in a G, C, E, and E tune settings. This unique layout gives the charango its distinctive sound and playing style. The strings are usually made from nylon or gut and each pair is tuned to the same note, creating a harmonic, chorus-like effect when plucked.

To play the charango, hold it firmly by the neck with your left hand. This can be done in either a seated or standing position, depending on your comfort. Your fingers should be positioned on the fretboard, ready to form chords. For beginners, it may be helpful to first focus on the G, C, and E strings, gradually incorporating the top E string as you grow more confident.

The charango’s small size and string arrangement make it somewhat similar to the ukulele. However, unlike the ukulele, the charango requires you to form chords using the third, fourth, and sixth strings. This difference can be a bit challenging at first, especially for those transitioning from the guitar or ukulele, but with practice, it becomes second nature.

Once you’ve mastered the chords, the next step is to develop your plucking technique. This is done with the right hand and involves strumming or plucking the strings while forming chords with the left hand. When done correctly, this produces a sweet, gentle sound reminiscent of a harp.

As you advance in your charango playing journey, you can start exploring more complex techniques such as tremolos, hammer-ons, and pull-offs. These techniques will add depth and flavor to your playing, allowing you to express a wider range of musical ideas.

One crucial tip for beginners is to practice regularly. Like any skill, playing the charango requires consistency. Even a few minutes of focused practice each day can lead to noticeable improvements over time.

Finally, remember that learning to play the charango is not just about mastering techniques, but also about expressing your own unique musical voice. So let your creativity shine, explore different musical styles, and most importantly, have fun! The charango is an instrument of joy and passion, and it invites you to discover the rich musical heritage of the Andean region.

The Sound of the Charango

The charango is more than just a musical instrument; it’s a conduit for the rich, harmonic melodies that capture the spirit of the Andean region. Its sound is as distinct as its history, imbuing traditional Andean music with a unique tonal quality that sets it apart from other stringed instruments.

The sound of the charango is shaped by its construction and tuning. Traditionally made from the shell of an armadillo and now more commonly from wood, the charango’s petite body and ten strings produce a bright, resonant sound that carries a surprising amount of volume for its size. The strings are arranged in pairs, each tuned to the same note, which creates a chorus effect that adds depth and richness to the instrument’s tone.

In traditional Andean music, the charango holds a place of honor. Its high-pitched, vibrant tone complements the lower tones of other traditional instruments, like the panpipes and drums, creating a harmonious soundscape that resonates with the spirit of the Andean highlands. The charango’s nimble, harp-like sound is perfect for playing the lively rhythms and flowing melodies that characterize this genre, lending the music a uniquely Andean flavor.

While the charango is deeply rooted in traditional Andean music, its versatility has allowed it to step beyond these borders and find a home in many different music genres. Its distinctive sound can be heard in everything from folk and pop to classical and jazz. This is a testament to the charango’s unique character; even when played in different styles or contexts, it retains its characteristic tone, adding a touch of Andean charm to any piece of music.

In recent years, the charango has also found a place in the world of film scoring and music production, where its unique timbre provides an excellent tool for creating atmospheric and evocative soundscapes. Whether it’s used to convey a sense of place, to add color and texture to a musical arrangement, or to create a specific mood, the charango brings a unique sonic palette that enriches the musical narrative.

The Cultural Significance of the Charango

The charango’s cultural significance is as deeply layered as the music it produces. An integral part of Andean culture and traditions, this small instrument plays a large role in the region’s musical tapestry. Beyond its musical contributions, the charango also serves as a potent symbol of identity, resilience, and cultural pride in countries like Bolivia and Peru.

Historically, the charango has been a central component of Andean folk music, providing the melodic backbone for many traditional songs and dances. It was often played during community gatherings, festivals, and rituals, its vibrant melodies echoing the spirit of the Andean people. Its music has been a thread weaving through the daily life of the Andean communities, marking everything from festive celebrations to quiet moments of reflection. In this sense, the charango is not merely a musical instrument, but a vehicle for cultural expression and communal bonding.

The influence of the charango extends beyond the borders of the Andean highlands, finding its place in a variety of music genres. Its distinctive sound can be heard in folk music around the world, adding an unmistakable Andean flavor. Similarly, it has found a place in the world of classical music, where its unique timbre is used to add color and depth to orchestral compositions. More recently, it has even found its way into pop music, demonstrating the instrument’s versatility and global appeal.

On a deeper level, the charango holds profound cultural significance as a symbol of national identity in countries like Bolivia and Peru. Despite its humble beginnings and modest appearance, the charango carries the weight of history, resilience, and cultural pride. It is a testament to the enduring spirit of the Andean people, who have maintained their cultural traditions amidst centuries of change and adversity. In Bolivia and Peru, the charango is more than an instrument; it’s a symbol of national heritage, a reminder of their rich history, and a beacon of cultural pride.

Today, the charango continues to resonate with the melodies of the Andes, captivating audiences around the world with its unique sound and rich cultural significance. As we listen to the music of the charango, we are invited to experience a piece of Andean culture, to understand its past, appreciate its present, and look forward to its future. Through its strings, the charango tells a story of a people, a culture, and a region that is as vibrant and resilient as the music it produces.

Notable Charango Players and Performances

The charango, a symbol of Andean music, has been played by many talented musicians throughout history, known as charanguistas. These individuals have not only contributed to the development of traditional Andean music but have also introduced the unique sound of the charango to other genres and audiences.

- Ernesto Cavour is one of the most influential charanguistas. Born in La Paz, Bolivia, he has dedicated his life to the charango, contributing greatly to its international recognition. Cavour is also a composer and has established the Center of the Charango in Bolivia.

- Jaime Torres, born in San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina, is another highly regarded charanguista. His mastery of the charango has brought him to perform at important festivals all around the world, showcasing the versatility of this instrument on a global stage.

- Eddy Navia, from Potosí, Bolivia, has made significant strides in promoting Bolivian music in the United States, with the charango being a key element of his performances. His work has helped to expand the reach of the charango and introduce its unique sound to new audiences.

- Hector Soto, a renowned charanguista from Quillota, Chile, has been recognized for his exceptional talent, winning the first prize at the Guitar Festival of Barcelona. His performances have helped to elevate the charango to the same level as other well-known stringed instruments.

- Rolando Goldman, an Argentinian charanguista from Buenos Aires, has used his music to bridge the gap between the traditional and the contemporary. He is also an instructor at the University of Buenos Aires, teaching new generations about the charango and its place in music.

Although these charanguistas come from different backgrounds, they all share a common love for the charango. Through their performances and recordings, they have greatly influenced the perception of the charango, demonstrating its unique sound and versatility to audiences worldwide.

While the charango has deep roots in traditional Andean music, its distinct sound has also found its way into contemporary music. It is this adaptability, combined with the skill and passion of notable charanguistas, that continues to elevate the popularity and respect for this unique instrument.

Evolution of the Charango

The charango, a treasured emblem of Andean music, has undergone significant evolution over the centuries since its conception. Its journey is a testament to the dynamic nature of musical instruments, reflecting the changes in societal and cultural contexts. In this chapter, we will discuss the transformation in the design and construction of the charango, the emergence of electric charangos, and the future directions for this unique instrument’s development.

Changes in the Design and Construction of the Charango Over Time

The charango’s story begins in the post-colonial era of the Andean region, a time when European stringed instruments were introduced by Spanish colonizers. It is a product of the cultural fusion between the indigenous Quechua and Aymara populations and the Spanish settlers. The earliest versions of the charango were crafted from the shell of an armadillo, known as quirquincho or mulita in South American Spanish. This distinctive choice of material was a result of a blend of necessity and ingenuity – the indigenous musicians lacked the technology to shape wood in the manner of the vihuela, the Spanish instrument that inspired the charango. The armadillo shell’s unique resonant properties also contributed to the distinctive sound of the charango.

Over time, as woodworking techniques improved and as armadillo populations became protected, the construction of the charango shifted towards wood. This change brought a new range of tonal possibilities, as different types of wood imparted their unique acoustic characteristics to the instrument. Various woods such as mahogany, maple, and chestnut became popular choices, offering not only their acoustic properties but also aesthetic variations. The design of the instrument also evolved, with the number and arrangement of strings varying across different regions and periods. The standard charango now typically features ten strings arranged in five courses.

Introduction of Electric Charangos and Other Modern Variations

As the charango journeyed into the 20th century, it began to encounter and incorporate modern innovations. One significant development was the introduction of the electric charango. Similar to the electric guitar’s evolution, the electric charango was born out of a need for greater volume and versatility in various musical settings. Equipped with magnetic pickups that capture string vibrations and convert them into electrical signals, the electric charango can be amplified and processed, expanding its sonic possibilities.

Other variations of the charango have also emerged. For instance, the charangón is a larger variant tuned an octave lower, and the walaycho is a smaller cousin tuned an octave higher. These modern variations have allowed the charango to adapt to a wide variety of musical styles, from traditional Andean music to contemporary genres like rock and pop.

Future Directions for the Development of the Charango

Looking ahead, the charango’s evolution shows no signs of slowing down. As globalization continues to facilitate cultural exchange, the charango is likely to encounter new influences that will shape its future development. For instance, advancements in material science could lead to the use of new materials in charango construction, potentially offering new tonal characteristics or environmental sustainability.

The future of the charango is also closely tied to the musicians who play it. As more musicians around the world discover the charango, they will bring their unique perspectives and influences, further enriching the instrument’s musical repertoire. This could lead to the development of new playing techniques, or even the invention of new variants of the instrument.

Moreover, as technology continues to advance, the digital realm represents a vast frontier for the charango. The incorporation of digital signal processing and synthesis could give rise to hybrid acoustic-electric charangos that harness the best of both worlds.

Instead of Conclusions: The Charango Family and its Variations

The charango family extends far beyond the traditional instrument that many are familiar with. A wide range of variations have emerged over time, each with their unique characteristics, adding a rich diversity to the world of charango music.

- Ayacucho: A miniaturized version of the traditional charango with a flat back and usually made from plywood. This smaller instrument consists of six strings arranged in five courses, and despite its size, it maintains the charango’s tuning.

- Bajo Charango: This is a larger bass instrument, leaning more towards a guitar than a traditional charango. This innovation was crafted by luthier Mauro Nunez in the Cochabamba region. Its large resonating body, typically constructed from plywood, and six strings arranged in five courses, give it a lower sound, two octaves beneath the charango.

- Charango Mediano or Mediana: This variant is a rural instrument that varies greatly in size and is usually tuned an octave below the traditional charango.

- Khonkhota: This rustic instrument is typical in the rural regions of Cochabamba, Oruro, and Potosí. It is characterized by a plywood soundbox and only five frets. It has eight strings in five courses, with each course maintaining unison doublings.

- Moquegua: This charango variation features 20 strings arranged in five courses of four strings each. Its tuning aligns with the standard charango, utilizing octave doublings for the central course.

- Pampeno: This is another rustic charango variation utilized in the Arequipa region of Peru. It has 15 metal strings triple-strung in five courses.

- Shrieker: A smaller instrument similar to the walaycho, typically constructed from wood or armadillo. It differs from the walaycho by having 12 strings, usually metal, in five courses.

- Sonko: A unique heart-shaped instrument with 13 strings. This instrument was first designed in the 1970s by Gerardo Yañez, and has yet to establish a standard tuning.

- Vallegrandino: Named after its town of origin, Vallegrande, Bolivia, this charango variant is about 50 cm long and has six strings in four courses.

In addition to these variants, there exist numerous regional variations of the charango, each with unique characteristics and adaptations to local music styles. These include the Anzaldeño, Ayquileño, Diablo, and the Sacabeño, among others. Whether it’s the “toy” charango or the heart-shaped Sonko, each of these variations contributes to the rich tapestry of charango music. Their diverse shapes, sizes, and tunings reflect the versatility of the charango and its adaptability to different musical traditions and preferences. The charango’s ability to evolve and inspire new forms is a testament to its enduring influence in Andean music.