The oud is a fretless stringed instrument, prominently featured in Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Greek, and Armenian music. Originating over a thousand years ago, it is often regarded as the predecessor to the European lute.

What is Oud: Table of Contents

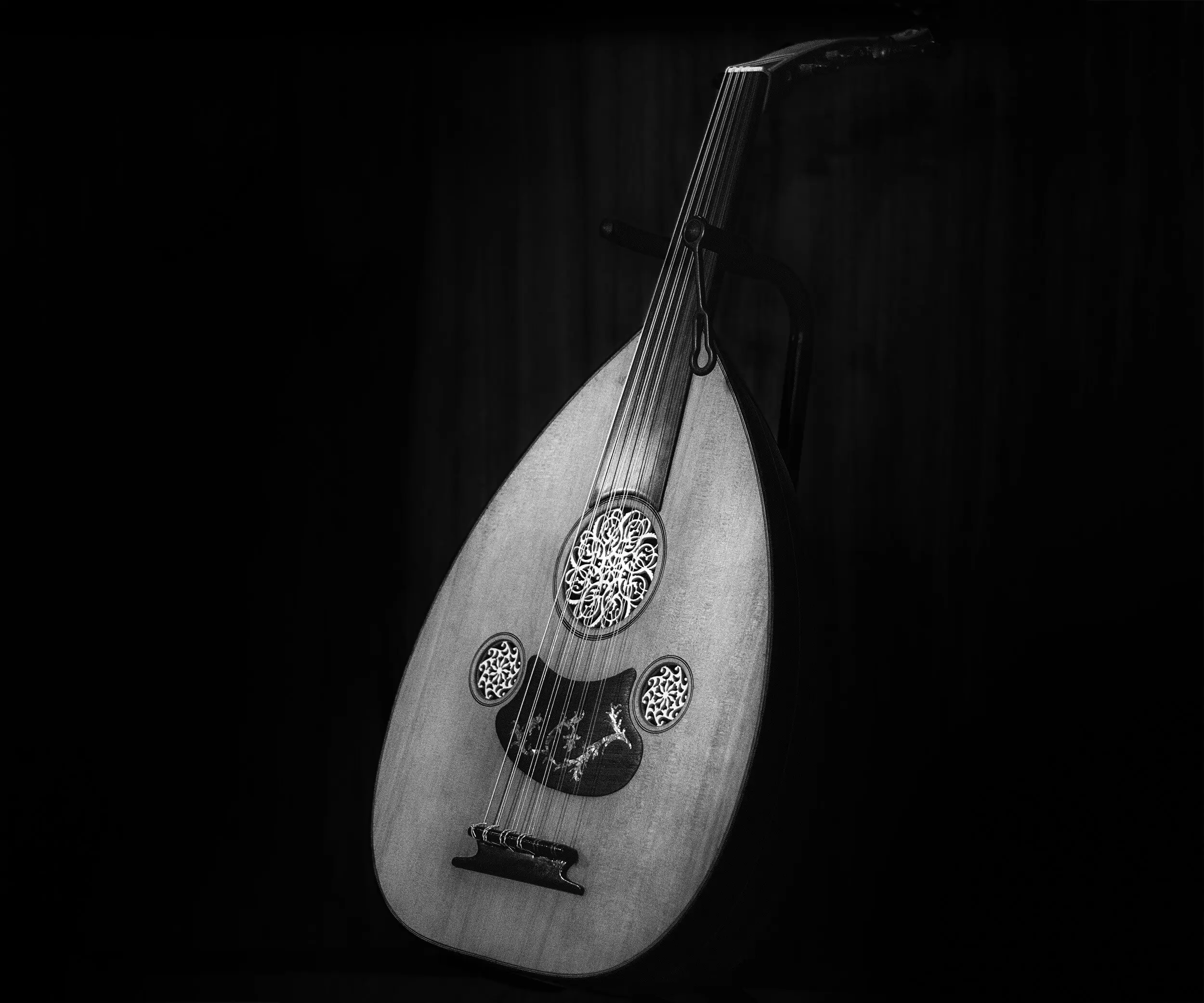

The oud, an instrument steeped in rich history and cultural resonance, holds a unique place in the realm of music. With a distinctive pear-shaped body and an extensive array of strings, the oud is a marvel in both design and function. Its deep, warm tones and intricate design are reflective of its origins, extending back several millennia to the ancient regions of Mesopotamia and Egypt.

The oud’s enchanting sound and deep cultural significance have established it as a cornerstone in traditional Middle Eastern music. As we journey through history, the oud’s influence echoes not only in the tunes of the Arab world but also in the diverse music of Europe, Africa, and Asia. Its enduring presence stands testament to its versatility and its pivotal role in cultural exchange across centuries and continents.

From a structural viewpoint, the oud is an embodiment of refined craftsmanship. Its peculiarly-shaped body, comparable to a pear or gourd, coupled with the careful selection of resonating woods for construction, contributes to its unique tonal quality. The intricate artistry involved in the creation of an oud is a captivating subject in itself.

Variations of the oud have emerged over the centuries, each with its own distinct characteristics. These variations primarily include the Arabic, Turkish, and Persian ouds, each bringing a unique flavor and texture to music. While they share common roots, the differences in their physical attributes and tonal quality have shaped distinct musical traditions. These variants will be explored further, as we delve deeper into understanding the fascinating world of the oud.

Roots and Etymology of Oud

The term “oud” is derived from the Arabic language and translates to “a thin piece of wood.” This might seem like a simplistic interpretation, yet it beautifully encapsulates the essence of this instrument – slender wooden staves elegantly fused together to construct the hollow body of the oud.

To trace the oud’s ancestry is to venture back through time, to the ancient Persian Empire. It’s widely believed that the oud evolved from an instrument known as the barbat. Introduced around the first century BC, the barbat shares striking similarities with the oud, both in structure and style. However, the barbat was characterized by its skin-topped body, a feature later replaced by wood in the evolution towards the oud. This transition marked a significant shift in the instrument’s tonal qualities and playing techniques, paving the way for the oud we know today.

In examining the grand tapestry of musical history, it’s crucial to acknowledge the relationship between the oud and the lute family of instruments. The lute, a central figure in Western music from the Medieval to the Baroque period, bears a striking resemblance to the oud. Music historians often regard the oud as the ancestor of the lute, noting the similar shape, string arrangement, and playing technique. However, unlike the fretted lute, the oud’s fretless neck allows for a broader range of tonal flexibility, which is essential for the microtonal music of the Middle East. This deep-seated connection links the musical traditions of the East and West, providing a compelling illustration of the power of music as a universal language.

Physical Structure of the Oud

The design of the oud is as much a work of art as it is a marvel of acoustic engineering. Let’s begin with the body. Picture a shape reminiscent of a pear or a gourd – this is the general silhouette of an oud. The material used in crafting the body is an essential part of its tonal signature. Most often, hardwoods are chosen to build the oud’s body, with varieties such as walnut, maple, padauk, and mahogany frequently utilized. These woods are favored for their durability and, crucially, their unique resonating properties.

Covering the body’s top is the soundboard, a critical component for the oud’s characteristic voice. Craftsmen often use softwoods like spruce for the soundboard, which serve as the primary resonating surface for the vibrating strings. The use of softwood provides an enhanced resonance, granting the oud its rich, warm, and voluminous sound.

Accentuating the aesthetics of the oud, you’ll typically find decorative elements adorning the sound holes. These sound holes, usually one large central hole accompanied by two smaller ones, are often framed with intricate designs known as rosettes or purfling. Beyond adding a touch of artistic flair, these embellishments also serve a functional purpose, contributing to the overall tonal dispersion of the instrument.

Turning our attention to the back of the oud, we encounter the resonator. This bowl-shaped structure is not unlike the design found in instruments like the Neapolitan mandolin, bouzouki, or balalaika. The resonator’s construction involves the painstaking process of gluing 15 to 25 individual staves of hardwood together, forming a beautifully rounded back. The use of hardwoods in the resonator’s design is essential in crafting the oud’s robust and full-bodied tone.

Every component, every piece of wood, every curve and angle in the oud’s physical structure serves a unique purpose – to shape the instrument’s sound. The oud’s distinct voice, rich with resonant lows, expressive mids, and delicate highs, is a direct result of the meticulous craftsmanship that goes into its construction. This harmonious blend of artistry and acoustics is what makes the oud an instrument of unparalleled beauty and tonal depth.

Stringing and Fretboard of the Oud

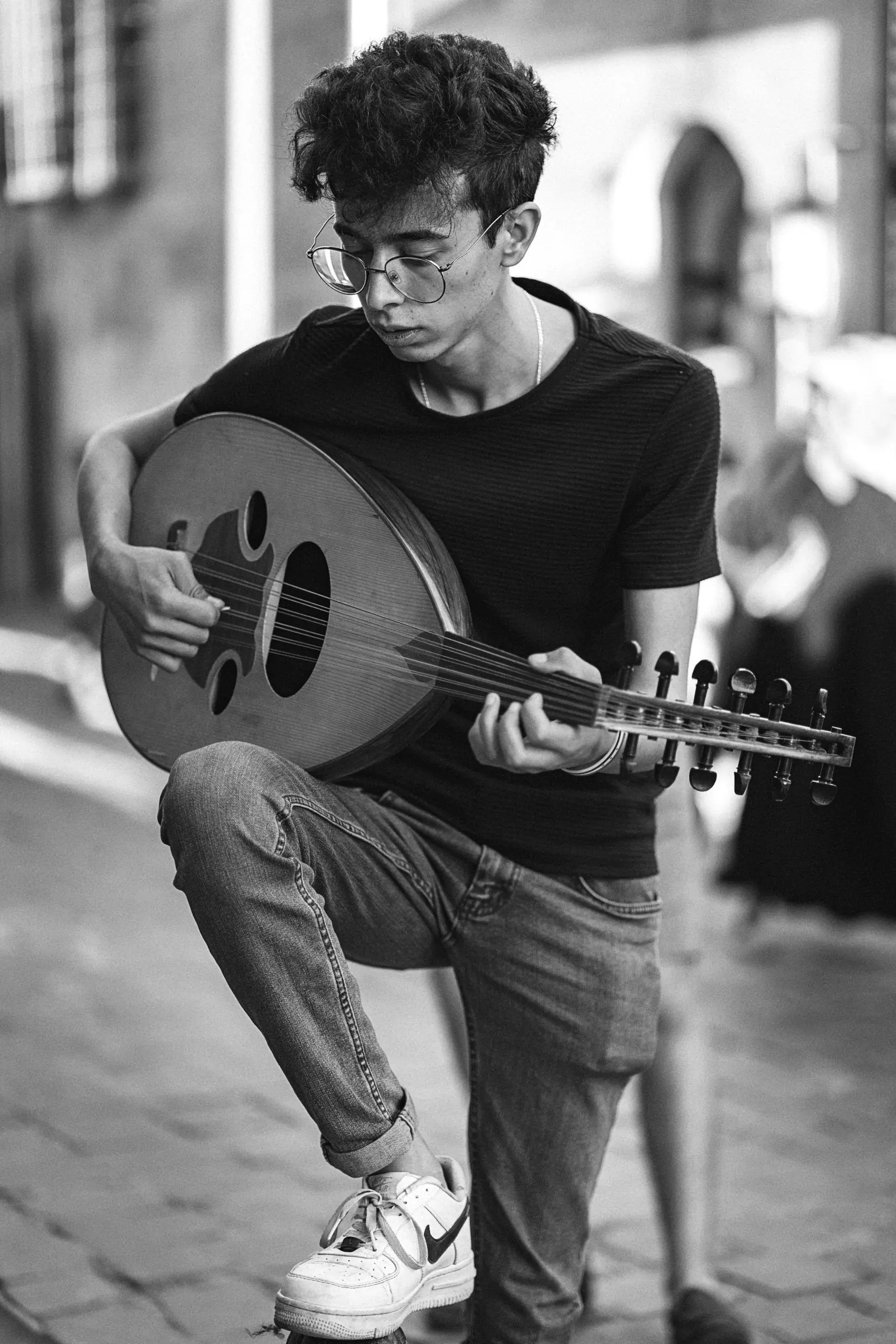

Upon closer inspection of the oud, one feature immediately stands out: its fretless neck. This element is not merely a design choice, but a crucial factor that influences the instrument’s playing style and sound. The lack of frets provides a continuum of tonal possibilities, allowing the musician to play a vast spectrum of microtones. This is a defining characteristic of Middle Eastern music, where notes often lie “between” the fixed pitches found on a piano or a fretted guitar.

Next, we move onto the headstock, a key component that ensures the oud’s strings stay in tune. The headstock is distinctively angled backwards, typically at 45 or 90 degrees, a design that helps to increase the tension of the strings. This increase in tension, coupled with the instrument’s unique scale length, contributes to the oud’s signature resonance and sustain.

Keeping these strings under proper tension are the wooden friction tuners, a feature that gives the oud its rustic charm. Functionally similar to the tuning pegs found on a violin, these tuners allow for precise adjustments to each string’s pitch. This mechanism is essential for the oud, as the ability to hold tuning stability is key for any stringed instrument.

An oud typically sports 11 strings, arranged in a unique configuration. This setup consists of one single bass string, followed by five pairs of strings tuned in unison. This results in a texturally rich sonic palette that gives the oud its wide tonal range and distinct voice.

The process of playing these strings involves using a pick, known traditionally as a risha. Historically, the risha was crafted from materials like eagle feather quill, bone, or wood, each contributing their unique textural qualities to the instrument’s sound. However, in the modern context, plastic picks have become commonplace due to their durability and consistency.

Tuning of the Oud

Tuning is an integral part of playing any musical instrument. With the oud, this process takes on a fascinating dimension due to its unique string setup and its significant role in a musical tradition that embraces a wide spectrum of tonal nuances. Adjusting the tuning of an oud to the preferred pitch is not merely about ensuring a pleasing sound—it is about allowing the instrument to fully express its captivating voice and facilitating the performer’s interpretation of a musical piece.

Arabic tuning is one of the most widely used tuning systems in the oud world. Starting from the lowest to the highest string, the tuning goes as follows: D2, G2, A2, D3, G3, C4. This pattern gives the instrument a rich, warm tone that lends itself beautifully to the expressive, often improvisational, nature of Arabic music. Additionally, some musicians may choose to substitute the G2 string for an F2, which offers a subtle change in tonal color and can inspire different melodic ideas.

Turkish tuning, on the other hand, presents a brighter sound, in line with the overall tonal characteristics of Turkish ouds. This tuning, ascending from low to high, goes as follows: C2, F2, B2, E3, A3, D4. These specific pitches give the instrument a unique character that complements the lively rhythms and intricate melodic patterns found in Turkish music. An alternative Turkish tuning pattern is D2, A2, B2, E3, A3, D4, which is also used widely and provides another tonal palette for musicians to explore.

Tuning an oud is not a rigid, unchanging process, but rather a flexible one that can adapt to the musical context, the specific instrument, and the musician’s preferences. By understanding the principles behind Arabic and Turkish tuning, one gains a deeper appreciation for the oud’s versatility and the richness of the musical traditions it embodies. This understanding also encourages a spirit of exploration, as the possibilities in oud tuning are as wide and diverse as the music it produces.

Variations of the Oud

The oud’s broad historical and geographical reach has given birth to several distinct variations. Each regional oud variation is a reflection of its cultural context, showcasing unique physical attributes and tonal characteristics that align with local musical aesthetics and traditions.

Arabic ouds are one of the most widely recognized and played variations. Notable for their larger size and longer scale length, Arabic ouds produce a deep, full-bodied sound that resonates with the soulful expressiveness of Arabic music. These characteristics are not uniform across all Arabic ouds, however. For instance, the Syrian oud, revered for its slight increase in neck length and a lower pitch, creates a unique tonal space that is both warm and rich. Meanwhile, the Iraqi oud, with its slightly guitar-like timbre, brings a different color to the musical spectrum, further demonstrating the diversity within the Arabic oud category.

Moving northwest, the Turkish oud exhibits a different set of attributes. Smaller in size and with a shorter neck compared to its Arabic counterpart, the Turkish oud generates a higher pitch and a brighter tonality. The low string action and close placement of string courses also set the Turkish oud apart, offering a distinct playing feel and sound. Despite its name, the Turkish oud is not confined to Turkey; it is also a favored instrument in Greece and Armenia, reflecting the shared musical influences across these regions.

Further east, we find the Persian oud, also known as the barbat. With its longer neck and smaller body, the Persian oud offers a different sonic character and aesthetic from the Arabic and Turkish varieties. One intriguing aspect of the Persian oud is its slightly raised fingerboard, a design element that accommodates a unique playing style. A nod to its ancient roots, traditional barbats were carved from a single piece of wood. Today’s instruments, however, are typically made from staves of mulberry or walnut, adhered together to form the rounded body.

Each of these oud variations—Arabic, Turkish, and Persian—contributes to the rich tapestry of oud music. They each tell a unique story of cultural exchange and evolution, playing an integral role in the diversity and depth of music in their respective regions. Yet, despite their differences, they all share the unmistakable character of the oud, with its captivating resonance and profound musical expressiveness.